In this blog post, we will explore the triaxial test, also known as the triaxial shear test. Geotechnical engineers regard triaxial tests as the holy grail among measurement techniques for smaller soil samples because these tests allow them to extract a wide range of crucial soil characteristics.

- History of the triaxial shear test

- Understanding the Triaxial Test

- How Are Triaxial Tests Used?

- Measuring Kits Used in Triaxial Tests

- What types of triaxial tests exists?

- What are common sources of error in relation to triaxial tests?

- Conclusion

- References

History of the triaxial shear test

The triaxial shear test or going forward the triaxial teat, was first developed by Arthur Casagrande, see Figure 1, in 1930 in an attempt to try and elucidate the strength properties of the soil media in all three primary directions. This also includes the loading history of the soil which has a significant role in the long term behavior and response.

When formulating the triaxial test Casagrande wanted to understand exactly how the soil specimen reacts to pressures from directions within the primary three ranges since soil strength and response behaviors are highly anisotropic.

Casagrande cup

He developed the ‘Casagrande’ test, which utilizes the Casagrande cup to quickly characterize soil strength parameters based on soil hydration.

As the water content within the soil is governing for the general characteristics it is important to try and understand relationships between water content and strength of soil to mention just one important correlation.

Understanding the Triaxial Test

A tri-axial test evaluates the strength of soil material characteristics in all three primary directions within a closed environment.

This allows for a complete description of the soil characteristics when subjugated to pressures typically seen during the lifetime of the soils and under different boundary conditions considering soil wetness. This is important in a wide variety of cases and we will explore some of these in the following but especially so when trying to establish some sort of structure on top of the soil.

How Are Triaxial Tests Used?

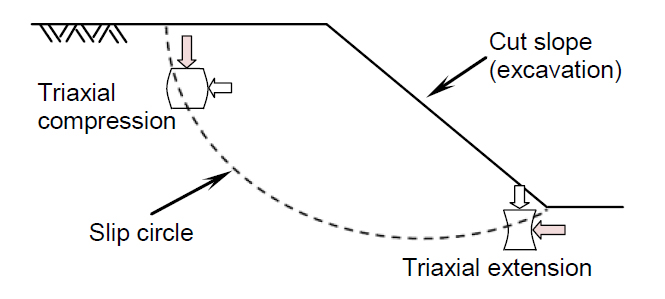

The triaxial test serves as the holy grail of geotechnical engineering, offering a wide array of applications as engineers seek to understand how soil structure responds to shearing. Table 1 outlines several common uses of the triaxial test, while Figure 3 illustrates one of these applications.

| Type of project | Typical analysis |

| Tunneling | UU – Unconsolidated Undrained |

| Excavation | UU – Unconsolidated Undrained |

| Marine structure (offshore wind) | UU – Unconsolidated Undrained |

| Foundation design of large structures | UU – Unconsolidated Undrained |

| Earth dams | UU – Unconsolidated Undrained |

| Cut slope failure | CU – Consolidated Undrained |

To elucidate the strength parameters of soils across a building site, engineers typically conduct multiple instances of the same test. This approach helps create a broader picture of the general characteristics of the underground soil strengths.

Consequently, the selection of test sites becomes a crucial part of the analysis, and it is essential to handle the samples with the utmost care.

Measuring Kits Used in Triaxial Tests

To conduct one of the common and characteristic tests on soil specimens, you need to acquire the right type of equipment and use appropriate measurement materials.

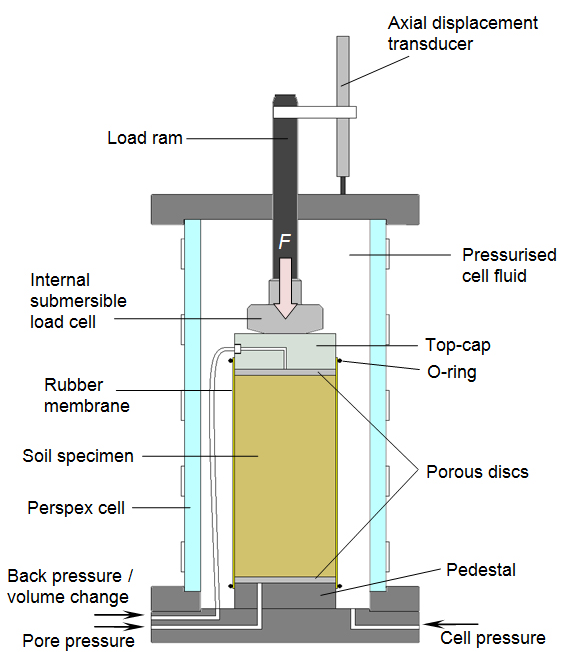

In this blog post, we won’t delve into the complete specifics of setting up the triaxial test. However, to enhance your understanding of the key features involved in carrying out the experiment and to clarify what knowledge you can and cannot extract from the typical experience, we present an example case featuring the pore pressure and soil sample in Figure 4.

From Figure 4, we can see that the triaxial test involves a comprehensive array of measurement equipment. Measuring pore pressures, soil actuators, and cell pressures plays a crucial role in the analysis, as these measurements enable the calculation of deviator stress and the B-value, which indicates the accuracy of the wetted soil sample.

Role of water

To establish an evenly distributed load across the soil sample, researchers critically utilize water.

Water plays a crucial role in the experimental setup, as we measure the individual pressures affecting the soil sample through nozzles and vents specifically designed for water pressures. By calculating pressures and pressure differences from these nozzles, we theorize how the soil structure responds to pressures from all directions.

The triaxial tests serve as an advanced measurement method for characterizing soil properties. This integrated approach to generating pressures, measuring pressure differences, and assessing soil water absorption has evolved over several years and remains an active area of research today.

What types of triaxial tests exists?

The various applications of triaxial tests are abundant and lead to different assumptions and usability cases. In general, we utilize three types of triaxial tests to evaluate the soil media, each focusing on different stress measures. These tests examine the undrained stresses related to both total stress from water and effective soil grain pressures, as well as effective stresses that consider only the interactions between individual soil grains.

Table 2 outlines the three different tests along with qualitative judgments on their accuracy and complexity. It clearly shows that the axisymmetric triaxial test, specifically the fast undrained unconsolidated test, is the simplest option, enabling us to clarify the total stress properties of the soil specimen.

| Feature | UU | CU | CD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drainage | Undrained | Undrained | Drained |

| Consolidation | Unconsolidated | Consolidated | Consolidated |

| Stress Measurement | Total stress | Effective stress | Effective stress |

| Complexity | Simpler | More complex | More complex |

| Accuracy | Less precise | More precise | More precise |

| Application | Short term behavior – Cohesive soils | Short term undrained behavior | Long term drained behavior |

Unconsolidated Undrained – UU

The three available tests highlight the unconsolidated undrained test as the fastest and one of the most commonly used types of triaxial tests. Understanding the short-term differences in soil strengths is essential, especially since geological processes can occur rapidly.

During construction, individual soil specimens often experience little to no consolidation, which means they bear the weight of both water and grains simultaneously.

Clay soils, in particular, exhibit high water adhesion and serve as the primary materials tested under unconsolidated undrained conditions. Their micro-scale grain sizes cause them to take significant time to expel water from their structure.

As a result, clays typically remain in an unconsolidated undrained state when subjected to increased pressure, a crucial factor to consider during the development of buildings and large infrastructures.

For a deeper understanding of clays and to explore the differences in soil structures among sand, silt, and clay, check out the following related readings for a comprehensive analysis.

Related reads: Stabilizing the Leaning Tower of Pisa: Engineering Marvels, Understanding clay characteristics across Denmark

As sand typically have a drainage capacity orders of magnitude faster compared to that of clay, it is typically not possible to undertake the Unconsolidated Undrained testing of sands as they will quickly drain and consolidate.

Consolidated Undrained – CU

Unlike the Undrained Unconsolidated test case, the Consolidated Undrained test case assumes that the soil has experienced significant pressures beyond the current pressures considered in the test. This condition allows soil particles to rearrange optimally, leading to soil compaction. When the soil undergoes this transformation, it is deemed to be in a consolidated state.

This type of test is typically more complex and time-consuming than the Unconsolidated Undrained test case. It is essential to ensure that the comparisons between soil strength based on effective stresses reflect the consolidated state and remain unchanged throughout the test under constant pressures.

Since consolidation occurs slowly, this triaxial test evaluates long-term issues that may arise during the structure’s lifespan after the initial construction phase, once the soil’s initial deformations have reached an equilibrium point.

This test presents a complexity that significantly exceeds that of the quicker triaxial UU test. Patience is essential for revealing the relevant aspects of the soil structure, and the risk of errors rises because the specimen must consolidate before consistently applying pressure. As the loading phase progresses, pore pressures build up and remain, causing some of the load to be supported by these excess pore pressures, which renders the test case undrained.

Consolidated Drained – CD

For the final of the three typical triaxial tests, we perform the consolidated drained test. This test is significantly more complex than the previous two. We must ensure that we consolidate the soil structure and apply the loading slowly enough to prevent excess pore pressure from building up during the loading sequence.

Maintaining consistency between pore pressure and cell pressure is crucial. This practice ensures that only the soil structure bears the load, allowing us to disregard the water content and drain it away. As a result, the soil structure alone supports the weight it experiences.

Related reads: The Role of Clay in Sedimentary Rock Formation

Soils with low grain sizes tend to adhere strongly to water, making drainage difficult and significantly slowing this step in the process compared to CU and UU tests. This is particularly true for fine-grained materials, where water content drains slowly during straining. To provide some time estimates, the UU test typically completes in under an hour, whereas CU and CD tests may take weeks to months to finish.

What are common sources of error in relation to triaxial tests?

Since skilled labor is necessary to accurately and safely conduct the required pressurized tests and handle the specimens in the triaxial test, we can reasonably assume that plenty of pitfalls may occur along the way.

Some of these pitfalls are easier to catch than others and that is where experience plays a key role as experienced users of the equipment have more resources to ensure a quality controlled conducted experiment compared with the inexperienced junior geotechnical engineers which may fall in classical easily avoidable pitfalls.

Conclusion

In summarizing the complexities and significance of the triaxial test within geotechnical engineering, it is evident that this method serves as an indispensable tool for evaluating soil strength and behavior under various conditions. From its historical origins with Arthur Casagrande to its evolution into a sophisticated measurement technique, the triaxial shear test offers valuable insights into the stress-strain responses of soils.

In this blog post, we examined the different types of triaxial tests—Unconsolidated Undrained (UU), Consolidated Undrained (CU), and Consolidated Drained (CD)—each playing a crucial role in understanding soil characteristics. We highlighted the significance of using proper measurement equipment and methodologies, emphasizing how the careful handling of soil samples and data collection can affect the results.

The applications of triaxial tests span a wide range of geotechnical projects, underscoring their relevance in foundation design, tunneling, and slope stability assessments. As the need for accurate soil analysis continues to grow, the triaxial test remains at the forefront of geotechnical measurement techniques, enabling engineers to make informed decisions in the pursuit of safe and sustainable structures.

References

Figures for the example excavation case for triaxial testing and test setup: “What is Triaxial Testing? Part 1 of 3” – GDS Instruments Manufacture Soil and Rock Testing Apparatus

Leave a comment